Here’s a secret Germans won’t tell you: Sometimes even they get tired of those big long words. Sure, they’ll post jokes about the never-ending nouns on their Facebooks and like all those joke memes on Twitter – especially that one about why Germans don’t play scrabble. But while they’re in on the joke of infinite infinitives, they too get tired of using them all day.

So they often shorten them but don’t tell the outside world.

They excel in what I’ve discovered are called syllabic abbreviations. Germans are syllabic abbreviation pros. A syllabic abbreviation is when you take the first syllable from each word in a series of words to form an abbreviation, which can then seem like an acronym.

Oh the taxonomy!

Syllabic abbreviations are such an integral part of German culture that they’ve leaked into other cultures too. All the way over the Atlantic, even!

Germans love syllabic abbreviations and I can prove it to you.

You know Haribo? That maker of spongy gummi bears? Syllabic abbreviation. It’s based on the company’s founder – Johann Riegel, who went by Hans. They took the first syllables of his first and last names and, because they apparently needed a third syllable, the first syllable of Bonn, where the company was based.

This created Haribo, or Hans Riegel Bonn. Cool, eh?

Syllabic abbreviations. I had no idea there was a term for it! I thought Germans were just making this up.

It gets worse – or better, depending on if you’re a glass-half-full or glass-half-empty type of human.

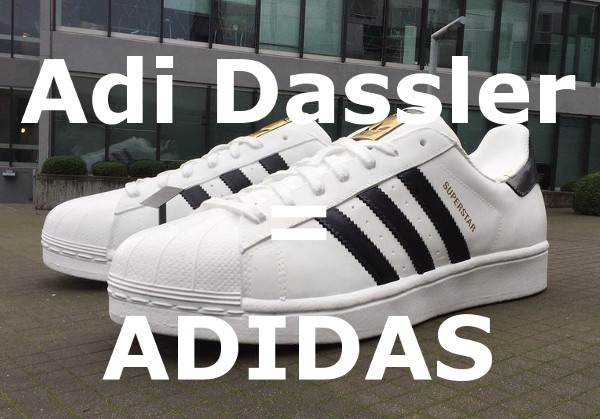

The Dassler brothers in pre-war Germany started a shoe factory in the sleepy village of Herzogenaurach, which is within running distance of Nuremberg. The brothers were named Rudi and Adi which, yes, is short for that German name no one wants to be called anymore. But Rudi and Adi didn’t get along and they divided the shoe company into two in 1948.

Rudi would end up calling his half of the company Puma – because how lame does Ruda sound? – but Adi called his – wait for it – Adidas (Germans pronounce it Ah-Dee-Dass, if you ever wondered). Adi Dassler! Adidas! Mind. Blown.

These are pretty common schoolyard truths in Germany. Just ask a German, they’ll tell you everything I just told you, but there’s one many Germans don’t even know: Milka.

Milka is Germany’s Hershey’s or Cadbury, if the chocolate actually tasted like chocolate and the packaging was always purple.

Even Milka’s cows are purple.

Full disclosure: I love Hershey’s because it tastes like Halloween and childhood and, come on, Hershey’s kisses y’all! But the first time I tried European chocolate it scared me. I was in third grade and snuck pieces of Toblerone at the Koernig’s house and it freaked me out – partially because I thought Mrs. Koernig was going to catch me and partially because it tasted amazing.

So amazing it scared me.

So Milka: It’s short for Milch Kakao (milk chocolate). Milka! I only learned this a week ago myself.

Oh there are more. Lots more. Hanuta is this great hazelnutty chocolate snack that’s a kind of cookie/candy bar thing that’s known as a Tafel in German. Hazelnut is Haselnuss in German so even you might be able to do that math: HaselNussTafel. Hanuta! They taste a million times better than they sound.

How about Aldi? No I’m not kidding. It’s owned by the Albrechts and the stores are considered discount – or Diskont – stores. Go on. Get some scratch paper and work it out. They’re taking over the world now so you’ll be able to use that one in the checkout line soon.

But these are just commercial examples. The German culture is filthy with other syllabic abbreviations. And by filthy I just mean they’re all over the place. Parents drop their kids off at a Kindertagesstätte (nursery) every morning, for example, but they call it a Kita. Some of those parents might work for – or be investigated by – the Kripo, or the Kriminal Polizei.

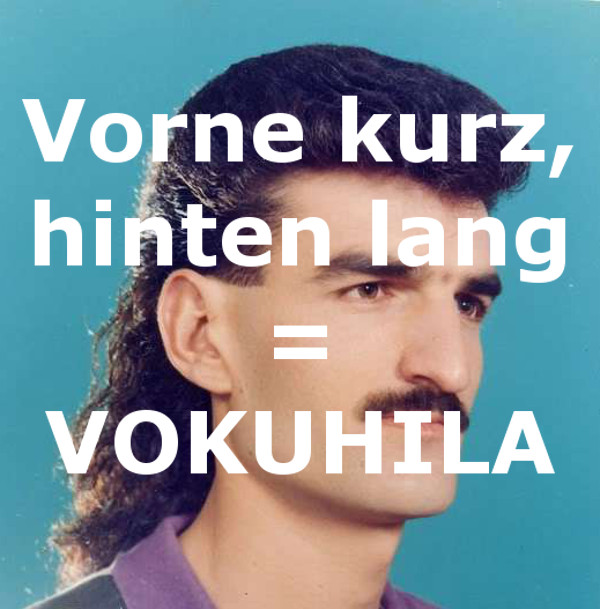

Oh! One of my faves when I first moved to Berlin was Vokuhila. Sounds exotic, right? It’s not. It’s German for mullet, that haircut favored by ‘70s soccer stars and the guy the changes the oil on my Chevy Tahoe. It’s short for: vorne kurz, hinten lang (short in the front, long in the back).

I liked that syllabic abbreviation so much I used to get my hair did at a salon called Vokuhila on Kastanienallee.

So there you go. German syllabic abbreviations are a secret no longer!

TschüLe (Tschüss Leute or good-bye y’all! Except that’s not a real syllabic abbreviation. I just made it up).

Secret to the people who read this far: Here’s one more that I cut from the blogpost but is kind of cool. So consider it a linguistic present from me to you. Because I really like you.

Edeka is a Berlin grocery chain that varies slightly from the basic scheme of syllabic abbreviation and that has a name with a bit of uncomfortable history (but not that history). Einkaufsgenossenschaft der Kolonialwarenhändler im Halleschen Torbezirk zu Berlin is what it stands for – the purchasing collective of the colonial goods dealers in the Halleschen suburbs of Berlin.

German, amirite?

Anyway, You get the “E” from Einkaufs…. The “de” from Der, the “k” from Kolonial and the “A” from thin air because apparently Edeko wasn’t what they wanted (but I think it sounds kinda cool).

8 Comments