One of the most unpleasant regular activities in Berlin is food shopping. Which is unfortunate, because I like to eat. Berlin grocery stores are crowded, disorganized and offer little variety, and that’s the expensive ones. The lack of variety is what annoys me most – I no longer even consider complex recipes because I know it’ll require stopping at three different stores and at least two weekly markets.

And let’s not talk about the discount grocers. Or, rather, let’s do. Before they built one right next to my apartment, I avoided discount chains like Aldi, Lidl and Netto as much as possible. Whenever I did decide to go shopping in one, I wondered if my life insurance covered discount-grocer related disasters. Their spartan stores are minimally furnished with white tile floors, fluorescent lighting and metal shelves, not to mention weird, hip-level cages for things every grocery shopper needs like socks or, last week, chainsaws (I’m serious). Most products aren’t unpacked from their transport boxes and are just stacked on shelves or directly on the floor, much in the same way a farmer drops a bale of hay in the middle of a paddock of hungry cows.

Aldi, Lidl are German grocery stores too

Variety is even worse in Aldi, Lidl and friends — I always run in hopeful that I can make spinach lasagna that night only to leave with just orange juice and cornflakes. The discounters are so bad that I’m convinced even the products are ashamed to be there. To be fair, the stores have improved some over my two decades in-country, but they’ve improved about the same as root canals have improved in that same period. It’s not as unpleasant as it used to be, but it’s still a root canal. But, yes, they’re cheap.

There are both cultural and economic reasons for the dearth of good food stores in Germany. The first is that Germans don’t like to spend money on food. They don’t like to spend money on much of anything, really, but that’s another blog post. Germany’s statistics office tells us that, when it comes to consumer spending, of each €10 Germans spend, only €1 goes to groceries. The French spend €1.33/€10 on edibles while the Italians spend €1.43. Romanians supposedly spend a third of their consumer outlays on sustenance, which sounds odd.

To put that in an even international-er perspective, according to a 2016 study by some agency called IRI, Germans spent €21.01 on a basket of food that would have cost €31.54 in the US, or €30.08 in Italy – quite a difference. Still, in the UK, which, in my experience had pretty good grocery stores, that basket cost just €22.14.

But the other reason German grocery stores are uncomfortable is the German inability to provide – or even a distaste for – customer service. It smarts in areas where companies are forced to offer some kind of service, like when a cashier is scanning your groceries. They quickly rip your items across the scanner and chuck them into the tiny area set aside for bagging. Although you can attempt to bag them as they leave the checker’s hand, the better strategy is to just grab whatever you’re buying and chuck it back in your cart (or basket) and bag them somewhere else – usually the most convenient place is the bus stop out front. Trying to bag your groceries at the cash register can slow things up and lead to disapproving looks and clucks from the cashier and fellow customers alike. The whole affair is so hectic it’s equivalent to half an hour on the free weights in the gym.

The pain of German groceries stores was acute last summer after we returned from two years in the US. Admittedly, the bounty in American grocery stores is alarming – is all that food actually eaten and who is coming up with things like cranberry-apple flavored kale chips? But the interaction with grocery store employees in the US feels like a family reunion compared to the battle of grunts and half-greetings you get from German grocery store employees. Consider this sample exchange between me and a checker in the US (it sort of went down like this):

Checker: Welcome to New Seasons! How are you?

Me: Good. Well, mostly good. Turns out a great aunt has cancer. How are you?

Checker: Good, only an hour left on my shift. My mother died of pancreatic cancer. Are these organic or traditional avocadoes?

Me: Sorry to hear that. Those are traditional avacadoes..

Checker: I’m sure it’ll be OK. That will be $34. Have a good day!

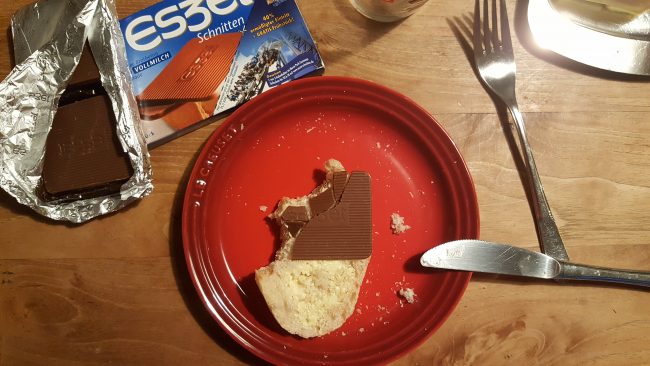

Maybe we should just stop cooking and eat German breakfasts for every meal. That would make it all a lot easier.